The Atlantic slave trade transformed the demographics of the Americas. Between 1500 and the end of the trade in the late 1800s, a little more than ten million Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas. These slaves came from dozens, or even hundreds, of different ethnic groups, cultures, and communities; in the slave societies of the Americas, they restored these heritages, but also remade and blended them in the formation of new identities and cultures.

In places of particularly intense plantation slavery — such as most of the Caribbean and Brazil — the majority of the population was of African descent by the 1800s. After slavery was abolished and these places became independent countries, these Afro-descendant populations demanded citizenship and mobilized politically as large and powerful constituencies. In places like Cuba and Brazil, this transformed the sense of national identity away from a Eurocentric one and towards an ideal of “racial democracy.” This ideal was often more a theory than a reality and Afro-descendant citizens still had to fight for recognition and rights; nonetheless, this ideal gave momentum to the demands of Afro-Brazilians and Afro-Cubans for real equality.

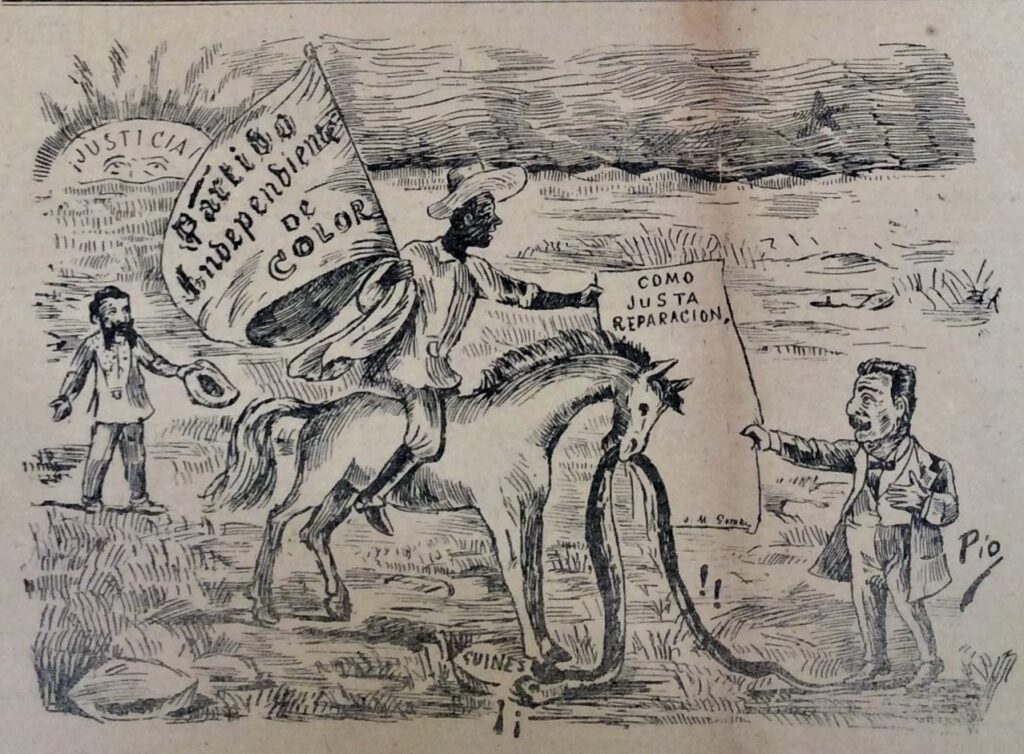

Political cartoon celebrating the Independent Party of Color (PIC) of Cuba. After Cuban independence, the government held the official stance that Cuba was a race-less, or post-racial, nation. However, many Afro-Cubans continued to face discrimination and formed the PIC to advocate for their rights. Despite the government’s anti-racist stance, it violently suppressed the PIC in the 1910s.

In other parts of Latin America, enslaved Africans were never a large part of the regional workforce. The slave trade brought Africans to every Spanish colony, but in many places — like Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, and Honduras — their numbers were few compared to the vastly larger indigenous population. When these colonies became independent countries and slavery was abolished in the early 1800s, those Afro-descendant populations became small racialized minorities within the national community.

In the early 20th century, all of the above-mentioned countries developed an official mestizo (or mixed-race) sense of national identity. Political, economic, and technological changes created the conditions for popular classes (working-class people, mixed-race people, and indigenous peoples especially) to become far more involved in the political process than had been permitted in the previous century. As these populations demanded representation — and as politicians attempted to appease these constituencies — the dominant ideas about national identity changed. No longer did political leaders say their nation was based on ideals of European whiteness. Now they said that their nation was an essentially mixed-race nation, a mestizo nation. But national leaders understood mestizo to mean a blend of Indian and European. This racialized sense of national identity did not include African descent. And it mostly still doesn’t.

With this theme, we are examining the tactics of Afro-descendant communities and activists to secure rights and recognition in such officially mestizo nations. You’ll be looking at two case studies: one concerning the Cauca region on the Pacific Coast of Colombia, and the other the Garifuna communities of the Gulf Coast of Honduras. In both of these places, Black communities and cultures are deeply rooted in the land and their foremost political concern has been securing land rights.

These Black communities are the descendants of runaway slaves. Everywhere where there was plantation slavery there were runaway slave communities. Some were small — a dozen or two people — but some grew very large and existed for decades despite the efforts of slaveowners to recapture them. These runaway slave communities (called quilombos in Portuguese, and palenques in Spanish) usually resided in remote mountain valleys, deep and dark forests, and difficult mangrove swamps — that is, natural geographies that were easier to defend or hide within when the slave-catchers and soldiers came. Some became integrated with indigenous communities, and developed their own governments, customs, traditions, and spiritual practices.

After national independence and the abolition of slavery in the early 19th century, persisting runaway slave communities became centers of Black culture. Because of both formal and informal restrictions on their movement, and because of their own efforts to stick together in solidarity, many Afro-descendant groups remained in well defined regional enclaves. Such was the case in the Cauca region of Colombia. Here, they developed self-defined traditions and throughout much of the past 200 years they largely lived self-sufficiently, producing their own food, necessities, and conveniences. They were neglected by the Colombian national government, which did little to support them, but this also meant they preserved a significant degree of autonomy that they zealously guarded from the encroachments of large landowners, multinational corporations, and the federal government.

The history of the Garifuna, as you’ll read in your third source, is a little bit more complicated, as they originated from the Caribbean island of St. Vincent. But, similar to the Cauca region, once the Garifuna arrived in Central America in the 1770s, their lifeways became integrated into the natural environment of the Mosquito Coast, as the region as known. For much of the last two centuries, the Garifuna homeland was of little interest to outsider entrepreneurs or the Central American federal governments, as it seemed to have little commercial value. The Garfiuna, consequently, were largely left alone. This has changed in recent decades, as the region became a valuable tourist destination and as international drug cartels warred for control in order to exploit the population through protection rackets. In the late 20th century, thus, the Garifuna were forced to defend their ancestral lands. These very local struggles, however, have taken on an increasingly global dimension and it is this that we will focus upon.

The big question:

How did Black activists attempt to redefine their identities in order to gain inclusion, rights, recognition and benefits from their nations and governments?

Sources

As with all of the themes, this one advances in four stages.

Stage 1

This source is a law, and it is therefore not easy to interpret. For the following Stage you will see how a scholar interprets it, but first we’re going to give it a shot ourselves. As a law, it describes an ideal or theoretical relationship between Afro-Colombians and the nation. How is this? How does it define the place of Afro-Colombians in the national identity? Keep in mind that this is a law that many Black activists fought to achieve for decades. What did they win?

Stage 2

In this reading, anthropologist Bettina Ng’weno analyses the 1993 law and how it fit into new senses of national identity and political solidarity that Black activists were mobilizing at the turn of the 21st century. As you read this, and when discussing it with your peers, go back to the text of the 1993 law. Do you see what Ng’weno sees in the law? How does she use wider context to give meaning to this law?

Stage 3

Stage 4

For this stage, you have two short primary sources. Please read them in the order they are presented here. The first is from an interview with a prominent Garifuna activist; the second is an excerpt from an international human rights case the Garifuna won in 2015. With each, we are looking for how the Garifuna used indigeneity (or indigenous-ness) to assert their interests and rights.